Howells Almost Restored Puddle Dock

by J Dennis Robinson

Portsmouth is unique. New Hampshire’s only seaport, soon to celebrate its 400th anniversary, blends charm and culture with vitality and commerce. In this series historian J.Dennis Robinson profiles people who influenced, honored, pictured, preserved, and promoted the historic architecture of “The Old Town by the Sea.”

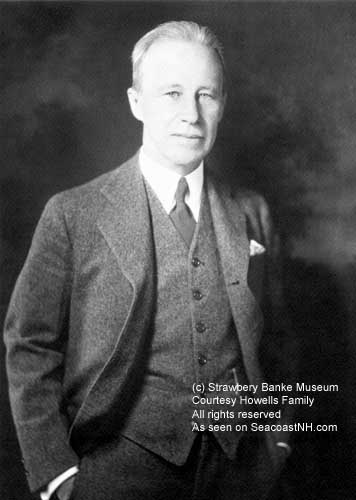

Architect John Mead Howells (Courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum/ Howells Collection)

He almost re-invented Portsmouth’s South End, but it was the right idea at the wrong time. During the 1930s, New York architect John Mead Howells (1868-1959) fell in love with the colonial structures that dotted the Piscataqua River region. Why not, he thought, restore the dilapidated buildings in Portsmouth’s South End and create an historic Maritime Park?

Once the beating heart of New Hampshire’s only seaport, the Puddle Dock waterfront had fallen on hard times. The federal government was ready to classify the run-down neighborhood, first settled in 1630, as a slum and tear it down.

John Mead Howells knew the area well. His famous father, essayist and playwright William Dean Howells, had purchased a summer home at Kittery Point in 1902. A prestigious editor at Harper’s and Atlantic magazines, Howells-senior entertained visiting literary lions including his friend Mark Twain.

John Mead Howells had gone on to become a well respected architect. He is best known today as co-designer of Tribune Tower, built in 1925, a Chicago landmark. Coincidentally the Chicago Tribune announced plans this year to sell the historic structure to a developer for an estimated $20 million.

His plan to save the ancient Portsmouth waterfront was elegant. First, Howells suggested, newer “ugly” structures built after 1830 should be moved to one side or destroyed. Then the older buildings, dating to 1695, would be restored to their former glory. Renting tenants could be trained to do the restoration work. The tenants would then be offered low interest loans to purchase the homes in which they lived. They would form a workforce that could then be trained to construct tall ships, replicas of the clippers and schooners that once sailed the Piscataqua region. Those tall wooden ships would then be sold to maritime museums. It was a visionary concept.

Portsmouth traffic heading to Kittery across Memorial Bridge, Howells also suggested, should be diverted through the restored historic neighborhood. Howells hoped to build a replica of the city’s 1760 State House that once stood in Market Square as a sort of visitor center and ticketing agency. Tourists motoring by might stop and purchase “strip tickets” to the city’s other historic house museums.

Howells and naval historian Stephen Decatur, also of Kittery Point, planned to lobby the idea to President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a national park. They needed federal funds to get the project started. But it never got off the ground. World War II intervened. In 1958, however, elements of the Howells/Decatur plan were recycled into the creation of Strawbery Banke Museum. Librarian Dorothy Vaughan, who had been a research assistant to John Mead Howells, became the first president of the new nonprofit 10-acre history campus. The Howells family in Kittery Point was a primary financial supporter of Strawbery Banke, now a popular heritage destination with dozens of restored buildings, each with its own story to tell.

In 1935 Howells published a photographic guide to the region. The Architectural Heritage of the Piscataqua, is now a classic–though not always historically accurate–reference to the beautiful early mansions of the region’s wealthy merchant class. A used copy of the often-reprinted volume can be purchased on Amazon.com these days for as little as one penny.

J. Dennis Robinson, is the author of a dozen history books including Mystery on the Isles of Shoals, available in local stores and online at Amazon.com. You can follow his history posts on Facebook here.

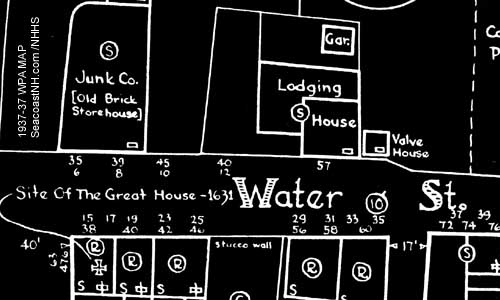

This 1936 WPA map shows a portion of a plan via John Mead Howells to turn Portsmouth’s dilapidated waterfront into a Maritime Park. Designed to preserve early architecture and create jobs during the Great Depression, Howells’ plan called for the restoration of 175 old Portsmouth houses and moving or demolishing 75 “ugly new buildings” (From the book Strawbery Banke by J. Dennis Robinson)

Architect John Mead Howells (Courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum/ Howells Collection)