Wallace Nutting Briefly Beautified Portsmouth

by J Dennis Robinson

Portsmouth is unique. New Hampshire’s only seaport, soon to celebrate its 400th anniversary, blends charm and culture with vitality and commerce. In this series historian J.Dennis Robinson profiles people who influenced, honored, pictured, preserved, and promoted the historic architecture of “The Old Town by the Sea.”

Wallace Nutting was way ahead of his time. In the early 20th century the former minister called Portsmouth “the most pleasing of all small shore cities.” Wallace invested in the charming, but tumbledown old seaport and photographed its grand colonial mansions. In 1916 Wallace bought the 1760-era Wentworth-Gardner House, one of Portsmouth’s architectural treasures, located in the city’s South End. The original owner, Mark Wentworth, was the son, uncle, and father of three royal governors of New Hampshire and was once the richest man in the province. Wallace bought and restored a number of other fading 18th century mansions from Connecticut, to Massachusetts, to New Hampshire. It was a costly task, but Wallace had no intention of losing money.

Wallace Nutting was way ahead of his time. In the early 20th century the former minister called Portsmouth “the most pleasing of all small shore cities.” Wallace invested in the charming, but tumbledown old seaport and photographed its grand colonial mansions. In 1916 Wallace bought the 1760-era Wentworth-Gardner House, one of Portsmouth’s architectural treasures, located in the city’s South End. The original owner, Mark Wentworth, was the son, uncle, and father of three royal governors of New Hampshire and was once the richest man in the province. Wallace bought and restored a number of other fading 18th century mansions from Connecticut, to Massachusetts, to New Hampshire. It was a costly task, but Wallace had no intention of losing money.

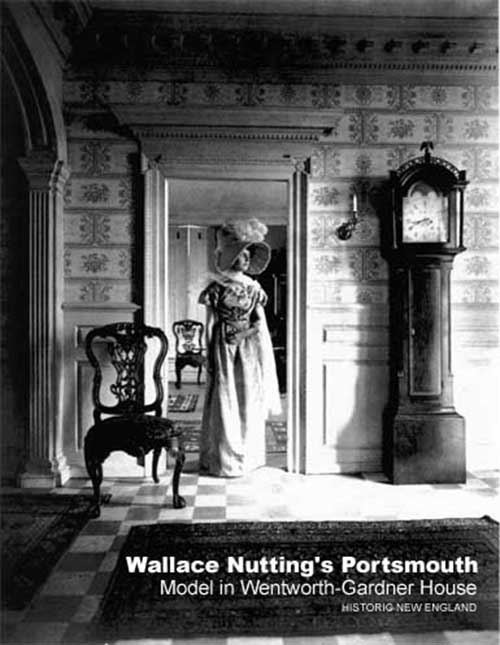

His idea was brilliant. He restored half a dozen colonial mansions and filled them with antiques. Nutting then used the beautified homes as the scenic backdrop for equally attractive photographs. He staged pictures with models in more-or-less period costumes. Nutting employed a small army of women to hand-color each black and white image. He sold an enormous number of photos. Buyers in the hectic Industrial Age were attracted to the romantic and pastoral images of a simpler (although largely imaginary) life of wealthy white merchant families before the American Revolution.

Recreating in motorcars–what we now call “heritage tourism”– was the latest fad in the early 20th century. Nutting charged visitors to tour the restored New England houses in his “Colonial Chain.” He wrote and illustrated history books that promoted his restored properties. He also manufactured and sold reproductions of the antiques that decorated his lovely homes, acting as a sort of Colonial Revival version of today’s consumer-oriented Martha Stewart.

Born in Massachusetts in 1861, Wallace Nutting spent his childhood in rural Maine. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard, then became an ordained minister. Nutting claimed to be neither artist nor historian, but rather “a clergyman with a love of the beautiful.” His eye for beauty and head for business made him a millionaire.

If the public could not afford colonial mansions, Nutting reasoned, they could at least afford mass-produced momentoes of the past. He sold them pictures, reproduction furniture and antiques. When motor touring faded, temporarily, during World War I, Nutting sold the Wentworth-Gardner House to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The MET planned to either move the structure or salvage its grand staircase and wood carvings. But a group of Seacoast residents saved the structure that remains a popular Portsmouth museum to this day.

Wallace Nutting came, he bought, he profited, and he sold out. He died in 1941. The famous antiquarian and entrepreneur preserved and marketed the beauty of Portsmouth’s colonial merchant houses at the dawn of automobile tourism. He also perpetuated an idealized vision of a past that had never really existed, spreading the Colonial Revival gospel to millions of willing buyers.

J. Dennis Robinson, is the author of a dozen history books including Mystery on the Isles of Shoals, available in local stores and online at Amazon.com. You can follow his history posts on Facebook here.

A black and white Wallace Nutting photo taken at the restored Wentworth-Gardner House in Portsmouth, NH. Courtesy of Richard M. Candee, author of Wallace Nutting’s Portsmouth: Photographs of the Colonial Past 1908-1918, Back Channel Press, 2007.