Sturgis Defined the Two Lives of Portsmouth

by J Dennis Robinson

Portsmouth is unique. New Hampshire’s only seaport, soon to celebrate its 400th anniversary, blends charm and culture with vitality and commerce. In this series historian J.Dennis Robinson profiles people who influenced, honored, pictured, preserved, and promoted the historic architecture of “The Old Town by the Sea.”

Well into the 20th century, residents of Portsmouth were often more inclined to tear down historic buildings rather than restore them. The city was conflicted. Should old structures be razed in the name of progress, or saved and repurposed?

Well into the 20th century, residents of Portsmouth were often more inclined to tear down historic buildings rather than restore them. The city was conflicted. Should old structures be razed in the name of progress, or saved and repurposed?

As architecture became a topic of academic courses in college in the 1880s, students and teachers began studying surviving buildings in seaport towns like Salem, Ipswich, Newburyport and Portsmouth. The first attempt to define the “build environment” of the city may be found in a rarely seen collection of essays called The Portsmouth Book, published in Boston in 1899. The lead article, “The Architecture of Portsmouth,” was written by Boston architect R. Clipston Sturgis. And yes, his analysis was as snooty as his name sounds.

In 1899 Sturgis described Portsmouth as having a “dual life” represented by two types of architecture. The first type was the “old life” of the city, a long-dead era of grand homes and walled-in gardens. Sturgis largely dismissed the “precious.” but “primitive” early Portsmouth architecture, exemplified by the surviving 1664 Jackson House.

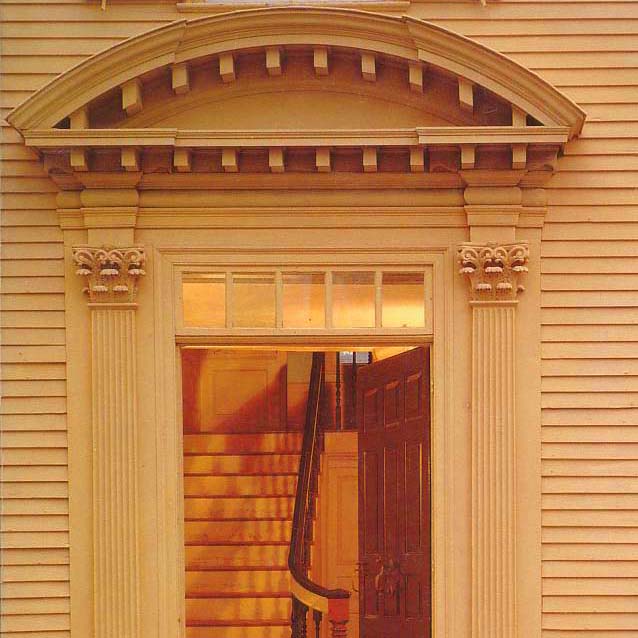

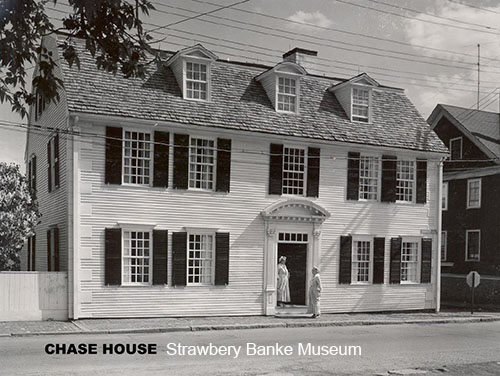

It was the larger homes of the 1700s that attracted Sturgis, unpretentious homes of good taste and refinement. By the mid-1800s, he wrote: “Riches meant extravagance and display, ostentation took the place of beauty, and for many years vulgarity seemed supreme.” His fascination was primarily with the grand homes of wealthy seaport merchants during the “golden age” of Portsmouth as a world trade center. Sturgis, typical of his era, was unconcerned with the enslaved people living in the attics of his favorite homes.

For Sturgis, the other half of downtown Portsmouth was the “modern life.” This was the architecture of hotels, stables, schools, factories, commercial and multi-family buildings. Modern Portsmouth, he wrote, was “little in touch with the old, having scant sympathy with its point of view.”

Thanks to the great fires of the early 1800s, in architectural terms, we have a brick Federalist downtown, dotted with Colonial, Georgian, and an eclectic mix of other styles. We are a patchwork city with some beautiful and some not-so-beautiful swatches. Sturgis’ essay is a good starting point for contemporary architects who search for ways to blend 400 years of history with the life of a bustling 21st century town. This mix of past and present may be at the core of why National Geographic recently rated Portsmouth as “the best small town in America.”

J. Dennis Robinson, is the author of a dozen history books including Mystery on the Isles of Shoals, available in local stores and online at Amazon.com. You can follow his history posts on Facebook here.

Richard Clipston Sturgis (1860-1951) described Portsmouth architecture in 1899 as having a “dual life,” half old and historic and half modern. Sturgis most admired the grand historic homes of the long-deceased and wealthy seaport merchants such as the Chase House seen here. (Photos courtesy Strawbery Banke Museum)